First there was mining. When the coal companies pulled up stakes and left their breakers to burn, plan B was manufacturing. When they left town, there was no plan C.

Where I grew up you could see the legacy of the defunct coal industry everywhere. Abandoned strip mines and mountainous ash piles were as omnipresent on the sides of highways as road signs. In junior high school, my basketball squad competed in the Anthracite league, and every few years we would all gather and watch one of the iconic coal breakers spectacularly reduce itself to dust in a torrent of flames.

After the post-war decline in anthracite coal mining, the community leaders in the region fought hard to continue to offer the opportunity of the American dream to its residents. In the 1950’s, civic economic development organizations invested heavily to attract manufacturing so residents and communities could grow and prosper without big coal.

I’m literally a product of that investment. My father was a foreman for more than 30 years in a manufacturing plant that wouldn’t have existed without the dedication of those forward-thinking community leaders. His job (along with my Mother’s restaurant) provided our family with a comfortable middle-class life and eventually, for my brother and I, college educations. I moved away from the coal region more than 25 years ago, but I still reflect on how its confines shaped my life and worldview.

When manufacturing started to leave in the 1990’s, people like my Dad were left scrambling for work, and those of us who grew up in these communities saw little opportunity to even equal the lives our parents enjoyed had we stayed. In addition to Hazleton, coal towns like McAdoo, Frackville, Mahanoy City, and Shenandoah have taken the brunt of those manufacturing losses. Throughout all of these towns, burned down and boarded up row homes are an all too common sight. As I walked through the ruins of the JW Cooper school in Shenandoah this past weekend, I couldn’t help but wonder how those of us who no longer live in Northeastern Pennsylvania callously left these communities behind.

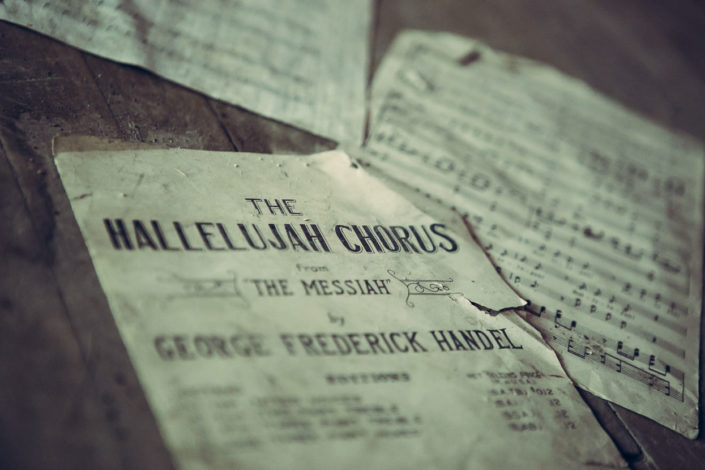

As a photographer, I’m frequently drawn to locations like this abandoned high school, but as a born and bred coal cracker it is becoming increasingly difficult to separate my artistic interest in theses decaying structures from their complicated societal underpinnings.

Part of me will always feel guilty for leaving. I didn’t stay and fight for a better future like those men and woman of the post-war era who stared down the loss of the area’s major industry and replaced it with another. I took what the coal region gave me and never looked back. When you’re on the outside looking in, it’s easy to identify blame for everything that’s gone wrong for this region during the past three decades. Being part of a solution is hard, just like anthracite coal and the people who mined it.

Photo Gallery

The J.W. Cooper Community Center is a 501c3 non-profit organization that is trying to restore the historical school for use as a community space. You can support their efforts here: www.jwcoopercenter.org.

Leave a reply